Energy firms and financial institutions have been eyeing LNG to power projects in Asia Pacific for some time but these projects have not materialised as anticipated. Of late, however, interest in developing these projects has resurfaced.

What has changed in the past several years? What are the challenges and opportunities facing these projects? This article touches on the key points discussed during our recent webinar with Ryota Kobayashi (Marubeni), Tom Wilson (Asian Development Bank), Yash Shah (Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation) and Tim Fourteau (White & Case) as moderated by Paul Harrison (White & Case).

LNG in Asia Pacific’s Energy Transition

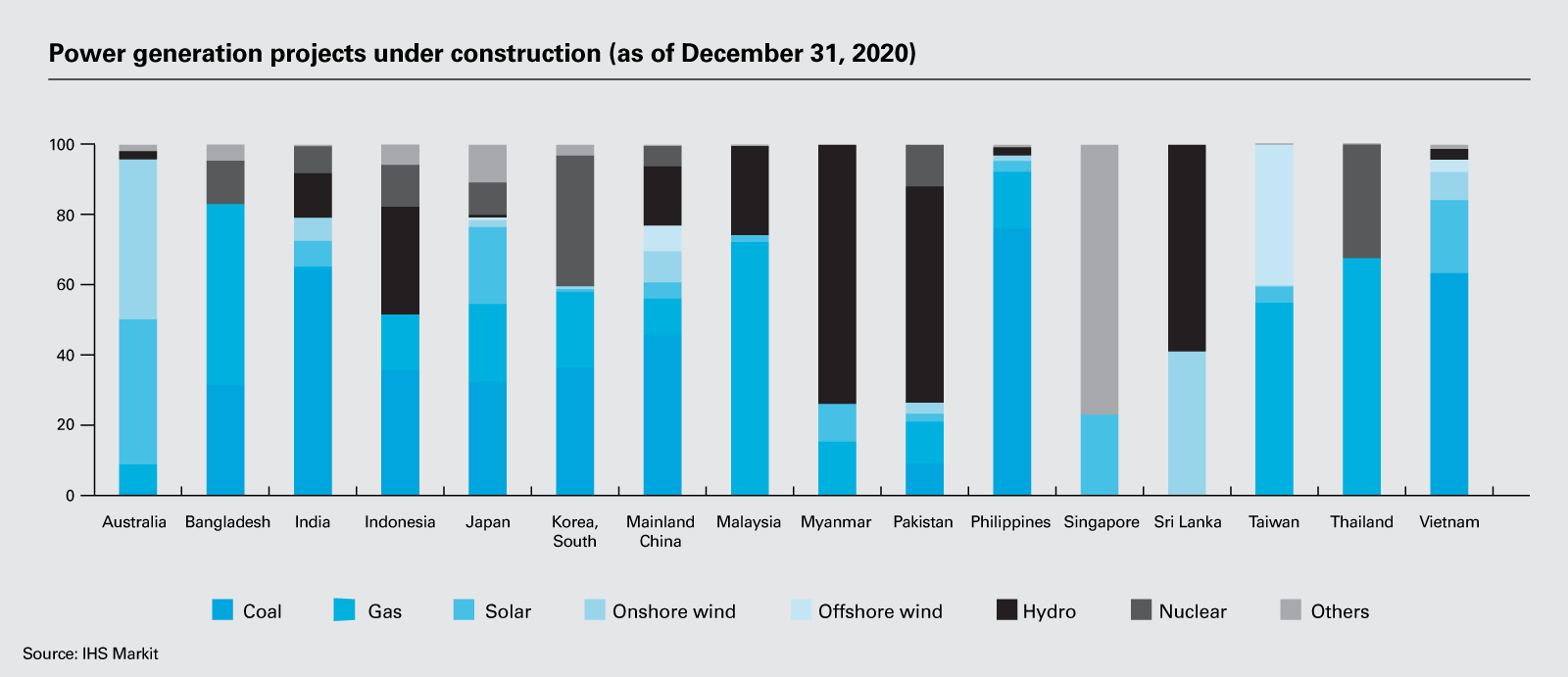

Many nations in Asia Pacific have traditionally relied on coal as the primary source for generating electricity due to lower costs and grid stability. However, coal power project development has generally slowed and focus has shifted to green energy options. While the role of natural gas / LNG to power in the energy transition is often questioned, gas is increasingly seen as necessary to enable a transition to low-carbon solutions without limiting economic growth.

“Renewable energy will no doubt be one of the major provider of power supply in Asia Pacific but there will also be demand for LNG and gas-fired-projects to ensure stability within the grid,” said Mr. Kobayashi. “Shell came out recently with their annual LNG report and they are forecasting a doubling of the current LNG demand by 2040 and more than half of that demand will be taken up by countries that have net zero emission targets. Clearly, those countries are seeing LNG as complementary to renewables in their forecasted power mix,” Mr. Fourteau added.

Recent Development in LNG to Power Market

While LNG-to-power projects in Asia Pacific may not have taken off as rapidly as the market may have anticipated several years ago, there are positive developments in the market over the recent years that the panellists believe will push forward progress on these projects.

“The role that a DFI Development Finance Institution can play in this transition is also in developing the distribution, transmission and the ancillary infrastructure, not least the grid. That is the role that ADB has been playing across a number of developing member countries in preparing the grid for the operation of major projects,” explained Mr. Wilson. “There is a lot of preparatory work that has been done and this has not been a “dead” period. A lot of policy decisions have been thought about and there is now positive movement to action some of these energy plans.”

In addition, there have been significant changes in the LNG market in recent years including the rise of traders, aggregators and portfolio players and a corresponding increase in the amount of shorter term and spot sales. This trend has resulted in the market demanding greater flexibility under the terms of LNG sale and purchase agreements, including with respect to pricing, tenor, volume and destination. Do these changes make it easier to move forward with LNG-to-power projects?

“LNG supply risk is a key risk that needs to be managed on these projects. The recent entry and development of aggregators and portfolio players helps manage allocation risk both on the upstream and downstream side. For example, if there are issues with liquefaction facilities, these players are able to tap on other sources of LNG supply. If there are issues on the downstream side, these players are also able to utilise reversionary or re-sale rights in LNG sale and purchase agreements to most effectively mitigate potential LNG oversupply risk,” said Mr. Fourteau.

On the flipside, however, volatility in the spot market, as seen in 2020 and the first quarter of 2021, may raise bankability concerns. Mr. Fourteau is of the view that aggregators will have a role to play in smoothing out that volatility, albeit not a full panacea given the long lead-time to mobilise LNG cargoes. The market is shifting on the power consumption side through market liberalisation, allowing the pass-through of feedstock costs to a greater extent than before. Mr. Wilson noted that the Philippines is a leader on this front with its merchant electricity pricing model.

What Needs to Happen Next?

In order to unlock the development of LNG to power projects, the panellists identified a number of roadblocks that would need to be addressed but noted that the challenges for each jurisdiction will differ. Mr. Kobayashi pointed out that “[what a project needs] heavily depends on the host country’s demand and what they actually need in terms of pushing [a] project forward.” Agreeing with him, Mr Shah added: “To paint everything with one brush is difficult; for instance, the Philippines and Vietnam are completely different.”

Role of the Government

To facilitate progress in these major projects, managing risk allocations as between the government, the developer and lenders is critical. The approach may differ for each country but certain risks should ideally be allocated to the host government. All panellists highlighted land acquisition and permitting as risks that would be difficult for the private sector to assume, as they are almost always out its control and may take years to complete. Another key issue would be the role of the government as the offtaker and the extent to which provisions under the power purchase agreement will be guaranteed by the host government.

“Especially for multi-billion dollar projects, the governments in certain countries will need to be more flexible and we have seen this in Indonesia. Originally [the market] started with a government guarantee with a kitchen sink approach and now [the market] is slowly and steadily moving towards accepting PLN risk,” Mr. Shah pointed out. However, in jurisdictions where government-friendly risk allocation positions have been accepted in smaller scale renewable energy projects, for example in Vietnam, Mr. Shah and Mr. Wilson were cautious that those governments may seek to impose similar risk allocations to LNG projects notwithstanding the greater project-on-project risks and capital investments inherent in these projects. As Mr Wilson noted, “It is going to be fascinating to see how this evolves and develops. These are much bigger projects with potentially a lot more political leverage. The Americans and Japanese are very engaged in terms of balance of trade.”

In addition, legal frameworks will need to be developed and refined to create a transparent and competitive market, which will have the flow-on effect of attracting strategic investors and sponsors for foreign capital and expertise. While governments across Asia Pacific do recognise the need for regulatory reform, implementing these changes with sufficient certainty typically takes time.

Mr. Fourteau raises the example of Vietnam to reiterate the importance of government support and direction. “Vietnam’s Public-Private Partnership laws for instance, show that the government is willing to encourage development, but it also raises questions whether there will be an availability of a government guarantee,” said Mr. Fourteau.

Mr. Shah agreed, explaining that clarity on government policy, energy plan and priorities will also be equally critical to accelerate the development of the LNG to power market. Focusing on certain potential projects that should be expedited and defining the risk allocation, project structure and scope will provide greater clarity to both developers and financiers to assess the feasibility and bankability of such projects.

Development of Infrastructure

Our panellists also examined the need for development of infrastructure such as power grids, gas infrastructure, pipelines and LNG import terminals throughout the entire chain through to the end consumer. Different jurisdictions however present unique challenges.

“The first elements of this is planning and understanding the legal, financial, commercial and physical environment,” said Mr. Wilson. “For instance, in the archipelagos of Indonesia and the Philippines, while there is an opportunity to bring in gas to power plants in those provinces and the presence of increased demand from population growth, there are also considerations of finding the right location to place the facility and the consideration of navigating shipping for those areas.”

While floating storage and regasification units (FSRUs) have been heralded as offering a quicker solution and have been adopted as the preferred option for a number of emerging markets, the panellists underscored the project on project risk that this approach would embody. Mr. Kobayashi noted that bringing down the scale of the projects, such as creating LNG hubs, would bring added layers of complexity and new risks, as well as competition with other forms of power generation such as diesel. This then has to be considered in the context of the need for more regulatory clarity as well as the lack of existing infrastructure to support such projects in provinces across archipelago nations.

Key Emerging Markets

In the short as well as the long term, Vietnam stood out as one of the attractive markets for the panellists. Mr. Kobayashi acknowledged that Marubeni is actively looking at this market in line with the significant growth in demand for power consumption expected in this region.

The panellists then went on to debate the potential in Indonesia where on the one hand, there may be limited scope for the development of new large-scale integrated LNG projects, but attractive opportunities may still exist for smaller scale projects using FSRUs such as in Bali, or power projects that may be required for mining facilities located in remote areas, given the new requirement to process metals in-country.

Looking to the rest of the region, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Myanmar were considered by the panellists to be potential players in the LNG to power market in Asia Pacific in the medium to longer term.

What was unanimous among the panellists was that the recent developments discussed above have firmly laid the groundwork for the rise of LNG to power projects in Asia Pacific in the coming years. Mr. Shah summarised the positive outlook of the panel when he concluded that, “reliance on LNG to power is going to be huge in Asia and development of these projects will accelerate.” There is certainly increased optimism that, despite previous false starts, Asia Pacific is now opening the window of opportunity for LNG to power projects.