I know, you probably haven’t even driven one yet, let alone seriously contemplated buying one, so the prediction may sound a bit bold, but bear with me.

We are in the middle of the biggest revolution in motoring since Henry Ford’s first production line started turning back in 1913. And it is likely to happen much more quickly than you imagine.

Many industry observers believe we have already passed the tipping point where sales of electric vehicles (EVs) will very rapidly overwhelm petrol and diesel cars. It is certainly what the world’s big car makers think.

Jaguar plans to sell only electric cars from 2025, Volvo from 2030 and last week the British sportscar company Lotus said it would follow suit, selling only electric models from 2028.

General Motors says it will make only electric vehicles by 2035, Ford says all vehicles sold in Europe will be electric by 2030 and VW says 70% of its sales will be electric by 2030.

This isn’t a fad, this isn’t greenwashing.

Yes, the fact many governments around the world are setting targets to ban the sale of petrol and diesel vehicles gives impetus to the process.

But what makes the end of the internal combustion engine inevitable is a technological revolution. And technological revolutions tend to happen very quickly.

This revolution will be electric

Look at the internet.

By my reckoning, the EV market is about where the internet was around the late 1990s or early 2000s.

Back then, there was a big buzz about this new thing with computers talking to each other.

Jeff Bezos had set up Amazon, and Google was beginning to take over from the likes of Altavista, Ask Jeeves and Yahoo. Some of the companies involved had racked up eye-popping valuations.

For those who hadn’t yet logged on it all seemed exciting and interesting but irrelevant – how useful could communicating by computer be? After all, we’ve got phones!

But the internet, like all successful new technologies, did not follow a linear path to world domination. It didn’t gradually evolve, giving us all time to plan ahead.

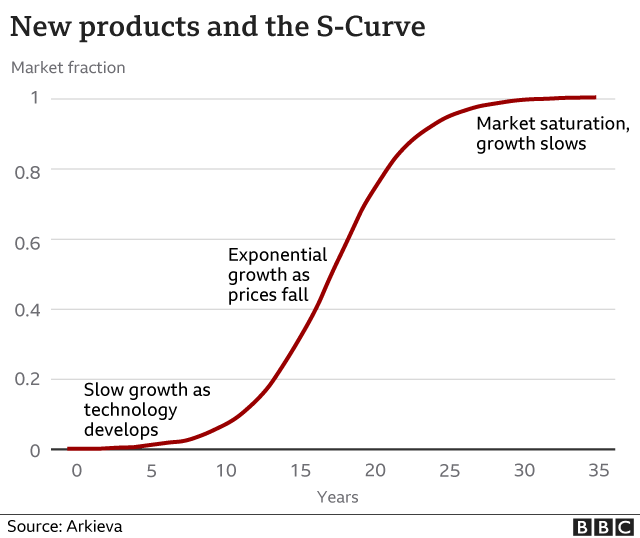

Its growth was explosive and disruptive, crushing existing businesses and changing the way we do almost everything. And it followed a familiar pattern, known to technologists as an S-curve.

Riding the internet S-curve

It’s actually an elongated S.

The idea is that innovations start slowly, of interest only to the very nerdiest of nerds. EVs are on the shallow sloping bottom end of the S here.

For the internet, the graph begins at 22:30 on 29 October 1969. That’s when a computer at the University of California in LA made contact with another in Stanford University a few hundred miles away.

The researchers typed an L, then an O, then a G. The system crashed before they could complete the word “login”.

Like I said, nerds only.

A decade later there were still only a few hundred computers on the network but the pace of change was accelerating.

In the 1990s the more tech-savvy started buying personal computers.

As the market grew, prices fell rapidly and performance improved in leaps and bounds – encouraging more and more people to log on to the internet.

The S is beginning to sweep upwards here, growth is becoming exponential. By 1995 there were some 16 million people online. By 2001, there were 513 million people.

Now there are more than three billion. What happens next is our S begins to slope back towards the horizontal.

The rate of growth slows as virtually everybody who wants to be is now online.

Jeremy Clarkson’s disdain

We saw the same pattern of a slow start, exponential growth and then a slowdown to a mature market with smartphones, photography, even antibiotics.

The internal combustion engine at the turn of the last century followed the same trajectory.

So did steam engines and printing presses. And electric vehicles will do the same.

In fact they have a more venerable lineage than the internet.

The first crude electric car was developed by the Scottish inventor Robert Anderson in the 1830s.

But it is only in the last few years that the technology has been available at the kind of prices that make it competitive.

The former Top Gear presenter and used car dealer Quentin Willson should know. He’s been driving electric vehicles for well over a decade.

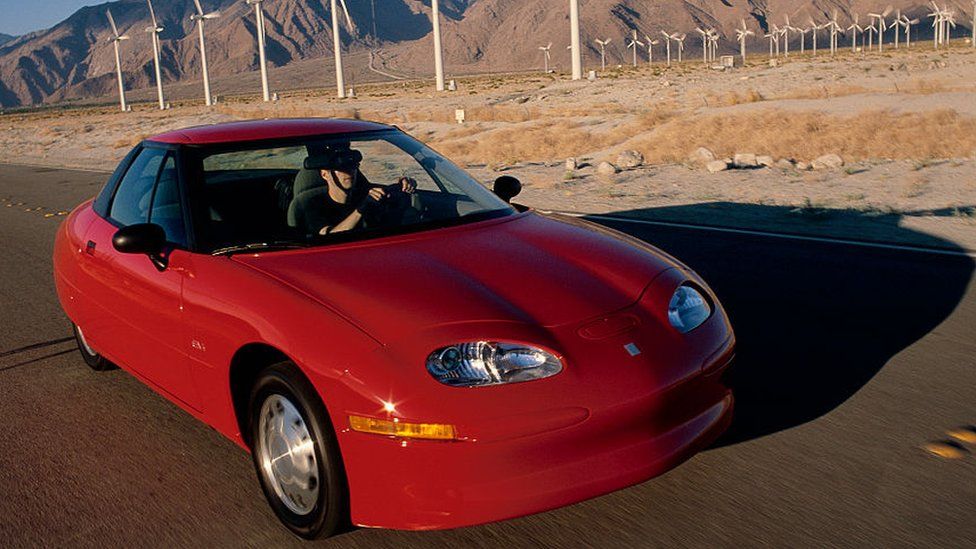

He test-drove General Motors’ now infamous EV1 20 years ago. It cost a billion dollars to develop but was considered a dud by GM, which crushed all but a handful of the 1,000 or so vehicles it produced.

The EV1’s range was dreadful – about 50 miles for a normal driver – but Mr Willson was won over. “I remember thinking this is the future,” he told me.

He says he will never forget the disdain that radiated from fellow Top Gear presenter Jeremy Clarkson when he showed him his first electric car, a Citroen C-Zero, a decade later.

“It was just completely: ‘You have done the most unspeakable thing and you have disgraced us all. Leave!’,” he says. Though he now concedes that you couldn’t have the heater on in the car because it decimated the range.