Furqan Akhtar, 36, a supervisor at the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board, had the task of doing discreet recces on his motorbike of streets in Manghopir, district West, and, upon spotting illegal hydrants, report them to the organisation’s water theft cell. KWSB personnel would then carry out raids to demolish those hydrants. One such operation in October lasted for 48 hours and resulted in seven illegal hydrants being dismantled.

According to the police report, on Nov 1, 2022, Furqan was waylaid by armed men while on his way back from the Manghopir filter plant after having had lunch there as per routine. They shot him in the head and made off with his motorbike. He was father to a six-year-old girl. It may have been a straightforward case of vehicle snatching — or not. Furqan’s family refused to speak with Dawn, citing security fears.

KWSB officials claim they’ve had violent run-ins with the owners of illegal hydrants while trying to shut down their operations. “One of them hit me with a big stone during a recent raid in Ayub Goth,” said a colleague of Furqan’s, touching the top of his head gingerly.

“I can still feel the depression in my skull. We had two or three police mobiles accompanying us, but they’re scared of the mafias themselves and do nothing.” After Furqan’s murder, the KWSB employee says, everyone at the office is unnerved. “Last Saturday, we were to carry out a raid against illegal hydrants, but we were stopped from doing so until we know more about who killed him and why.”

Illegal hydrants are one component of a monumental racket that revolves around the supply of water through tankers in Karachi. A very conservative estimate drawing on various sources and empirical evidence suggests the water tanker business rakes in at least Rs62 million on a daily basis from no less than 32 million gallons per day (MGD) of water ferried across the city in tankers. And this figure takes into account only six legal hydrants in the city.

Political VVIPs, government functionaries, KWSB personnel, military personnel, hydrant contractors, tanker owners, police, Rangers, community level strongmen/political workers are all part of this massive profitmaking operation. Instead of being an equitably shared resource, water has become a commodity, sold to whomever can pay the price.

But as Dawn Investigations discovered through site visits and interviews (most interviewees, given the nature of the topic, preferred to remain anonymous), the situation is far worse, with some quarters even more unaccountable than others — a true reflection of the kleptocracy that Pakistan has become.

“Access to water is a privilege, not an essential right of Karachi residents,” says academic and researcher Dr Noman Ahmed. He cites “social and political connections, influence of KWSB Union staff, local influentials and other power wielders” as being critical factors in citizens’ access to water.

There are six ‘official’ water hydrants in Karachi — NIPA, Sherpao (near Steel Town), Safoora, Manghopir (often referred to as the Crush Plant hydrant), Sakhi Hassan and Landhi hydrants. Their management is auctioned to private contractors for two-year periods, with the next auction process starting from Jan 26. (In the next cycle, some changes to location, procedure, etc are on the cards.)

There are two other hydrants that lie outside this auction process. One is in Baldia, district Keamari, which is operated on the ‘deputy commissioner quota’ and meant exclusively for the use of residents of Baldia and Orangi localities, areas severely impacted by water shortage. The other is the NEK hydrant in district East, run by the National Logistics Cell (NLC) whose operations — handled by a serving major — are virtually autonomous of the KWSB, the government body that legally has jurisdiction even over the city’s subsoil water. (The above estimate of at least 32 MGD per day delivered through tankers does not take NLC tankers into account.)

Karachi’s official water quota is 650 MGD; given its population, there is an acknowledged shortage of at least 450 MGD. In fact, a recent Nespak survey confirmed that the amount of water that actually enters the city is around 520 MGD. This comes largely from three sources: the Indus-fed Keenjhar lake, the Haleji lake — both in Sindh — and the Hub dam in Balochistan.

Availability of water in the dam — which supplies mainly to the sprawling, low-income Baldia and Orangi localities — is completely dependent on runoff water from the Kirthar Range. A network of canals, conduits, pumping stations, filter plants, K2 and K3 bulk mains, conduit lines, etc brings the water from these sources to Karachi. The KWSB oversees its management and distribution. One-third of the amount ends up as ‘non-revenue water’, ie water that is pumped and then is lost or unaccounted for.

In December 2016, in response to a constitutional petition filed by lawyer Shahab Usto, the Supreme Court set up a commission of enquiry to look into the provision of clean water to residents of Sindh as well as sanitation issues in the province. The commission was earlier headed by a serving Sindh High Court judge, Justice Mohammed Iqbal Kalhoro, and later by retired SC judge Justice Amir Hani Muslim.

It submitted four reports to the apex court on its provincewide findings. Where Karachi’s water supply was concerned, the commission found a state of anarchy, and 30pc operational losses “due to poor network of water supply lines, unchecked pilferage and illegal water hydrants”.

In the section on water hydrants, the second report noted that they “are running without any laid down rules and regulations.It was also seen that the process of contracting out the hydrants is quite inappropriate. The last process of tendering was done in 2008 and 2009. The fixation of prices is also very arbitrary. Among its 14 recommendations to improve this sector, it said: “The entire hydrants operation should focus on public service with a clear intention of serving to the deprived areas.”

Following these reports, for the nth time in the city’s history, and under pressure from the SC, a number of illegal hydrants were demolished. Government-sanctioned hydrants were brought down to six, which were to be auctioned “transparently” in accordance with public procurement rules.

At each hydrant, flow meters would quantify the water gushing into the tankers and cameras on the premises would bolster this ‘transparency’. But the situation on the ground is a far cry from this. A senior KWSB official says: “All the meters are tampered with. They take as much water as they want. There’s a KWSB person posted at each official hydrant to cross-check by counting the number of trips. But when they’re mixed up with them, how can you get a correct figure? Imagine, the water board can’t even manage the meters at its six hydrants!”

The SC-mandated water commission ordered the dismissal of an executive engineer at KWSB, Nadeem Kirmani, on allegations of corruption — including tampering with flow meters — but he was reappointed to the same post a year later and remains there to this day. He is also staff officer to Najmi Alam, vice-chairman KWSB.

On Sept 8, 2016, a Supreme Court order by a two-judge bench hearing a set of petitions against illegal hydrants in Karachi mentioned KWSB official Rashid Siddiqui as “being responsible for contracting out hydrants unauthorisedly”, and directed that a departmental enquiry be conducted into his actions. Instead, Mr Siddiqui was placed in charge of the water board’s anti-theft cell and remained there until recently. During his posting, it was alleged, perhaps not surprisingly, that he was in the practice of carrying out fake operations against illegal hydrants.

(Incidentally, when the Dawn team approached the Sherpao hydrant, which is currently the principal source for tanker service to DHA, one of the men on site began to record the vehicle on his cellphone. An armed guard then strode up and told the team to stop taking pictures and not come closer.)

MD, KWSB Syed Salahuddin Ahmed, concedes that meters at the hydrants are indeed tampered with. “But we’re inserting some good safeguards after the upcoming auction,” he says.

“The entire fleet of tankers will be under surveillance through cameras at each filling point … access to which will not be given to meter division. It’ll be third party monitoring.” He added that trakkers are being installed in the tankers, and there’ll be a computerised slip with a QR code “so the consumer can tell if the water is coming from where it is supposed to”.

As a result of the Sindh water commission’s comprehensive enquiry, winning the contract for running a hydrant now requires a bank guarantee of around Rs30m, bank statements for three years, tax returns, asset record, data of drivers, police verification, etc. But this appearance of an organised framework is deceptive.

The ‘ringleader’

Political heavyweights continue to dictate the mafia’s workings and nothing has changed — except that KWSB itself is now officially complicit in the fraud being perpetrated on the residents of the city. It is systemic corruption at its ‘best’. Only a handful of individuals have the resources to win contracts for operating hydrants, and mutually beneficial understanding with the top echelons of the city’s political and security apparatus is key.

A hydrant contractor tells Dawn he pays huge amounts in protection money. The bhatta goes to law-enforcement personnel, KWSB officers and those who oversee the operation at the highest level and their political patrons.

Several sources spoke of a “ringleader”, the son-in-law of a retired top provincial bureaucrat, who runs at least two official hydrants either directly or through front men, has a share in a third and is behind several illegal ones as well. “He manages all our maslay masaail (problems),” says an individual closely connected with hydrant operations.

So unaccountable are the characters involved that when a dispute arose in late 2017 over the auction of the Sherpao hydrant between two contenders, one of the parties took a stay from court, but the above-mentioned ringleader continued to operate it regardless.

The evidence is clear from satellite images of the period during which there was a stay on the hydrant’s operation. In April this year, the dispute was said to have been resolved and the hydrant operations ‘bought’ for Rs7 billion by the son of a well-known criminal lawyer and PPP senator.

The same ringleader also had two extra filling points installed at the Manghopir hydrant for the benefit of a PPP MPA from Tharparkar, ostensibly to provide water to KANUPP (Karachi Nuclear Power Plant) but according to KWSB sources, no questions are asked of him as to where the water is actually delivered.

There is also the ‘DC quota’ where, in the words of a disenchanted KWSB official, “the looting is even more than expectation”. It began innocuously enough in 2015 when a severe heatwave hit Karachi, and KWSB sanctioned several hundred tankers under the DC quota to provide free water to public venues such as mosques, imambargahs, etc to allay the effects of the scorching temperatures.

Over time, this has become for the Sindh government a convenient means of political patronage — even an alternative to providing jobs for party workers — in which local level PPP office-bearers, but also some from PTI, MQM and ANP, get tankers of water absolutely free. These tanker quotas range upwards of 50,000 gallons per day.

According to a hydrant contractor, a PPP leader prominent in Karachi politics, and who also holds a senior KWSB post, boasts the biggest daily quota — 300,000 gallons. For these fortunate souls, these tens of thousands of gallons of precious water are theirs to do with as they please — fill their swimming pools, water their lush lawns, bestow on friends, or indulge in their own tanker business on the side. This cushy arrangement would certainly be imperiled were power to be truly devolved to the third tier.

All the six official hydrants as well as the one in Baldia are obliged to fill the DC quota tankers. The Sindh government foots the bill, via the KWSB, for payment to the hydrant contractors. But huge amounts are outstanding and hydrant contractors, who have incurred expenses on this operation, have gone to court over it.

For example, Sher Mohammed, the contractor of the Sakhi Hassan hydrant, has filed two suits for recovery of Rs1,471,513,221. Ghulam Nabi, who runs the NIPA hydrant and has been in the business the longest, is suing the Sindh government and KWSB for recovery of outstanding dues of Rs191,114,404. In total, the sum claimed by the six hydrants is a mind-boggling Rs3,758,293,707. Even if this is an exaggeration, it indicates the kind of money involved.

Meanwhile, the NLC’s NEK hydrant receives no scrutiny. It did not find a mention in either of the water commission’s two reports. “Let alone senior KWSB officials, even the chief minister wouldn’t dare question its officers,” says a source in the water board.

On the NLC website, the ‘Road Freight’ section shows a ‘water services’ component. It reads: “With an overall capacity of about 324,000 gallons, this segment is actively engaged in provision of clean water to government and commercial organisations in Karachi.”

At the NEK hydrant, located in district East, the supervisor, named Nisar, told Dawn that the hydrant “only provides commercial services”. Sources in KWSB confirmed that unlike the hydrants in the hands of private contractors, the military-run NEK is not required to supply water to government organisations nor fulfill the DC quota. In other words, it is free to engage in the most lucrative chunk of the business. Many locations in DHA are provided water through NLC tankers.

The tankers standing under the filling points at the NEK hydrant were all painted with a distinctive NLC logo, but there were also over a dozen ‘regular’ tankers parked nearby. When asked, Nisar said they were used “when there is more demand for water than the NLC tankers can meet”.

Far from being a profit-making enterprise, the tankers were originally intended to supply water to NCL projects and installations. In the Sept 8, 2016 Supreme Court order cited earlier in this article, the MD, KWSB is quoted as saying, “[O]ne hydrant for NLC … needs to remain operational for strategic reasons.”

VVIP beneficiaries

All hydrants are billed at 40 paisas per gallon. There are two official sale price categories — General Public Service (GPS) and commercial. At the time of the 2020 auction of the hydrants, the GPS was set at Rs1,300 for 1,000 gallons, but hydrant contractors of their own accord last year increased it to Rs1,700 for 1,000 gallons; KWSB has yet to notify this rate. GPS slots are limited (although as per the KWSB’s contract with the hydrants they are meant to be 40pc of the total) and only available if booked online.

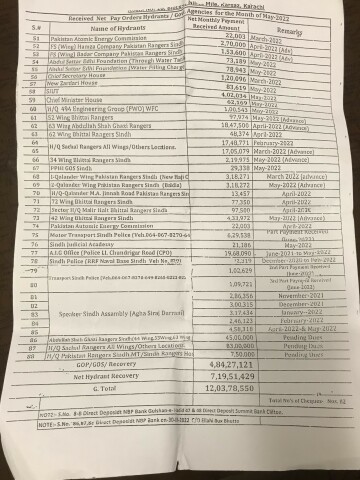

When hydrants are contacted directly, which most people are compelled to do, they are charged the commercial rate — Rs2,600 for 1,000 gallons. Thus, the largest share by far of hydrant sales is on commercial rates, because that also applies to apartment blocks and of course commercial/industrial establishments. NLC rates are even higher at Rs3,000 for 1,000 gallons. Dawn has obtained from KWSB sources a list of received net pay orders from hydrants and government agencies.

The KWSB’s recovery in May 2022 from hydrant operations is recorded at Rs71,951,429, with a break-up of receipts from each hydrant — except for NLC.

However, KWSB’s recovery from the hydrants in no way reflects the actual amount of water drawn. An official who was formerly in charge of the hydrant cell contends that 40 MGD of sweet water is delivered from six hydrants through tankers. That amounts to each of these hydrants earning Rs1.6bn per day, Rs48bn per month, or Rs576bn per year.

The water board’s MD, Mr Ahmed, concedes that the system has been very loosely run, “intentionally, so that [certain] people and not the department, make money from it.” According to him, KWSB earns Rs60-70m per month from the hydrant operations, whereas it should be at least 200 per cent more. He gave 18MGD as the official figure for the amount of water drawn by the six hydrants.

There is another point to consider. As per Census 2017, Karachi has 2.14m houses with a source of potable water, ie piped water connections. (There is no corresponding data available for commercial establishments.)

Taking Rs400 as the average monthly KWSB bill per unit, the total potential recovery amounts to Rs856.52m each month, which represents an increase of more than 1,000 per cent what the Board collected in May 2022 from six hydrants. And these recoveries were not for that one month alone but included partial arrears as well.

The water board could thus make far more if allowed to function as a civic body providing an essential service. But then, powerful stakeholders would lose an enormously lucrative source of income.

‘Ordinary’ citizens should also be outraged at the inequity in the rates they pay for tankers. KWSB provides tankers to a number of beneficiaries/locations at the GPS rate of Rs1,700 per 1,000 gallons; these dues are paid directly to KWSB by the Sindh and federal governments. Included in the list are Chief Minister House, Governor House, Chief Secretary House, New Zardari House, Bilawal House, PAF Korangi Creek Base, HQ 494 Engineering Group FWO and various wings of the Sindh Rangers etc. Some well-connected individuals figure on the list as well, such as Sindh Health Minister Azra Pechuho and Sindh Speaker Agha Siraj Durrani. A boutique owned by the daughter-in-law of a close business partner of PPP leader Asif Ali Zardari is listed among the beneficiaries, though the billing address is of the boutique’s ‘godown’ in Old Clifton.

Alongside the plunder of Karachi’s water through ‘official’ channels, illegal hydrants are also thriving. A brief clarification is in order here. Hydrants are of two kinds: those on the KWSB supply lines and those extracting sub-soil water. This investigation, for reasons of space, focuses on the first category, although many tankers are also supplying water drawn from sub-soil hydrants — a practice that presages an environmental disaster for Karachi.

According to a list compiled by NAB, there are at least 86 illegal hydrants drawing sweet water from the KWSB pipelines across the city. Of these, 75 alone are in district west, parts of which had become no-go areas some years ago because of militant activity and remain dodgy today.

Research by the OPP-RTI senior manager and his team in the second week of December on part of the list determined the locations of 10 illegal hydrants on KWSB supply lines in district West. Some areas such as Janjal goth, Mullah Hassan goth and Ramzan goth were considered too dangerous for the survey.

Some illegal hydrants, such as the one near Mashallah Coach Adda in Altafnagar, Orangi, are located within walled compounds. The hydrant comes into action when water is released in the pipeline. It is then diverted into huge underground tanks, from where it is sold through 1,000 to 2,000 gallon tankers — often to residents of Orangi itself. Such operations cannot take place without active connivance of senior bureaucracy and law-enforcement agencies.

Criminal rackets do not operate in silos. They intersect with and reinforce each other. The second JIT report looking into the murder of urban planner and social activist Perween Rahman, who was herself slain in district West, states: “[T]he members of the water mafia were powerful and well-connected individuals, who had relationships and affiliations with criminal elements across the board in Karachi, from the Lyari gangs to the MQM, to the [Pakistani] Taliban.”

According to Fahim Zaman, former administrator Karachi, “In a city like this, crime spreads like cancer, vertically and horizontally. Raheem Swati, who was convicted of Parween Rahman’s murder for reasons related to land grabbing [though recently acquitted on appeal], was also running an illegal water hydrant not far from the OPP office.”

“Dealing with illegal hydrants is risky work,” says a KWSB employee. “And no matter what we do, they come up again within a few days.” The fact is, there are enough powerful stakeholders in the hydrant business to keep it going uninterrupted. For instance, far from the badlands of district West, there is even an illegal hydrant along main Shahrah-e-Faisal, on land that is core to the national interest.

Consider too, the devastating cost to the environment and the country’s foreign exchange reserves. Assuming, very conservatively, that there are 7,000 tanker trips each day covering 140,000 kilometres in total, it adds up to diesel consumption of 23,000 litres and pollution amounting to 5.2 metric tonnes on a daily basis. Financial outlay at the current official exchange rate is around $700,000 per month, or nearly $8.4m annually.

Control of the megacity’s resources

The story of how the supply of water has evolved into one of the biggest rackets in the metropolis echoes the city’s political fortunes. Perhaps misfortunes is a more apt word. Since the mid-80s, Karachi has repeatedly been convulsed in bouts of extreme violence between various ethno-political groups — not to mention a fratricidal conflict within the MQM — vying for control of the megacity.

By the mid-2000s, its spoils were largely in the hands of the MQM, with its breakaway faction MQM-Haqiqi and the ANP staking control in some areas. Up until that point, however, water was not such a contested resource. In fact, hydrants first came about in the 1980s from a sense of political responsibility, to ensure that tankers supplied water to those parts of a rapidly expanding Karachi where pipelines had not yet been laid down.

In 1999, the city administration gave the 36 hydrants at the time to the Sindh Rangers to manage. “The Hub dam had been at dead level since the year before because there had been no rains,” says a retired bureaucrat. “Riots over water had started breaking out. What the Rangers did was to build huge storage tanks in various locations in the city, which were filled by tankers, from where residents could obtain water for free for their household needs.”

“No political force had the guts to interfere,” says a former KWSB MD. “Uninterrupted and equitable distribution — there was water for all without political disruption.” According to the same official, between 2004 and 2008 there was plenty of water and no real rationing was necessary. “The water tanker owners cultivated links with law-enforcement personnel during these four years. Maybe that’s how the Rangers acquired a taste for corruption.”

In 2008, Karachi mayor Mustafa Kamal put an end to the Rangers’ role, claiming that the MQM-led city government would operate the hydrants on the basis of tenders. Instead, the change opened the door to the law of the jungle.

“There were no tenders. Politically powerful groups forcibly took control of hydrants in areas under their influence,” says a retired bureaucrat. Thus, the ANP ran the hydrant in Banaras, MQM-Haqiqi in Landhi. The lion’s share went to the MQM and its head honchos; at least three MQM-controlled hydrants — in NIPA, Shah Faisal Colony and Garden East — were being run by the front man of a former mayor from the late ‘80s. With the coming of the PPP’s Sindh government, another stakeholder joined the racket.

The KWSB had no control over the hydrants; and earned virtually no revenue from them. From around 2011, the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan also became active in the racket. Reportedly, one of the biggest players in the hydrant mafia, Mushtaq Mohmand, aka Mushtaq water tanker wala was killed in a shootout in 2013, along with four other persons, allegedly because of his failure to pay protection money to some TTP factions.

An essential civic function thus morphed into a cutthroat business, in which there was plenty of water to provide to those willing and able to pay, but the taps often ran dry for millions who did not have the wherewithal.

Local strongmen & KWSB linemen

However, the tanker mafia cannot be looked at in isolation, for it is symptomatic of a much larger problem — the breakdown of the contract between the state and citizens. KWSB’s piped water supply system is shambolic, although the network of pipelines extends through much of the land falling in KDA’s jurisdiction.

Ms Khan, a university lecturer in Block 6, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, suffered for five years during which her street received virtually no water in the lines. If they wanted water, they would have to buy it from the NIPA hydrant, located less than a 10-minute walk away.

“When we complained to the KWSB, we’d be told there’s shortage in the bulk supply although we could see tankers lining up to be filled,” she says. “But every single water board person I’ve spoken to says, ‘just don’t mention the hydrant’.”

Things improved slightly this year after women in the neighbourhood raised a ruckus with the KWSB and also had a blocked pipeline cleaned at their own expense.

Testimonials from across Karachi echo the same refrain about the struggle for water. Collective action and the clout of local ‘strongmen’ appear to make some difference.

A comparison between two low-income areas, both within Baldia, illustrates this point. Hamid Mahmood, a driver employed with a local company, lives in Ittehad Town, where the population is largely Pakthun and Punjabi. “We get water in the line once a week for one hour regularly,” he says.

“That’s because dumper owners Kher Zaman and Nawal Khan live here. They have Kalashnikovs and everyone is scared of them.” When water is about to be released, a staccato banging on the lampposts serves as a signal for everyone to stock up on the scarce resource.

Abdul Sattar lives in another part of Baldia where residents are predominantly Memon, Kathiawari and Kutchi. “It’s a very divided community and people tend not to share information with their neighbours. Water comes in the pipeline once a month, sometimes twice, for an hour,” he says. “We only find out if someone we know is greasing the palm of the valveman [at the local pumping station] to release the water.”

In Clifton, close to Ziauddin Hospital, an individual known locally as Mahmood Gutkawala has managed, through contacts in KWSB, to get a six-inch pipeline placed through the water from Port Grand near Natives Jetty.

At the point where it emerges on land, a motor, operated through an illegal electric connection or kunda, connects the line with the distribution network for onward supply to Generalabad locality. Those operating the system told Dawn that each household is charged Rs300 for monthly costs — including the salaries of the three linemen involved.

Pervez Khan, a resident of Korangi No. 3, has water round the clock in his line even without the use of a suction pump. “Someone comes around to collect Rs500 per month from each house in the locality,” he says. The printed receipt he gets for the payment is not issued by the KWSB, but by a mohalla committee. Printed at the bottom of the slip is the cell number of a KWSB lineman.

Thus, while KWSB officials complain there is no more than 20pc recovery of bills from katchi abadis, in many places residents are paying water dues — except not to the KWSB.

If lower KWSB staff like linemen have such local ‘arrangements’ in place, one can imagine what munificence the water board itself bestows on powerful customers. About 40 km from Karachi, adjacent to the Dumlottee-K2 interchange, is a pumping station drawing water through two 12“ connections exclusively for Bahria Town Karachi (BTK).

This is believed to be one among six connections that the water board, without following due procedure, has given the real estate developer for its mammoth gated project at the cost of the Karachi residents downstream. Sources say that the KWSB MD at the time, following orders from his political bosses, called the top executives into his office and directed them to sign off on the connections in total violation of the prescribed process.

The board itself has yet to approve and notify the connections. That is but a seemingly irrelevant detail. For services rendered, the KWSB MD at the time has reportedly been employed post retirement as a consultant by Bahria.

Incidentally, of the original Dumlottee wells constructed by the British in the late 19th century — there were at least 10 of them — which were fed by the Malir river, only one is still in in use, though it supplies not more than a mere 1.4 MGD. The others have either been levelled or have dried up because of falling groundwater levels. Most of what is being diverted to BTK comes from the K-II bulk supply.

Also in district Malir is Memon Goth where several members of Karachi’s elite have farm houses. Among them is a PTI politician with a 350-acre farm, where the space, which includes a swimming pool, cottages and function halls, can be rented out to the public.

The owner has his own villa there as well, with its own swimming pool. The manager said the water for the facility is obtained through borewells, but seemed unable to recall where they were located. An attendant at the owner’s private villa, however, said the water in the swimming pool “belongs to KDA”. The KWSB bulk main runs very close to the area.

A considerable amount of Karachi’s water supply is lost far before it even reaches the city’s outskirts. All along one side of the 29km Gujjo canal that rises from the Keenjhar lake, 120 km from the metropolis, are huge fish farms on land belonging to Sindhi feudals, among them the politically prominent Shirazis of Thatta district.

“The SHOs and SPs in this area are appointed on their say-so. Who’s going to stop them?” says a man working near the Keenjhar lake, adding that diesel-powered pumps are used to draw water from the canal into the fish farms under the cover of night. “You might even find the pipes still lying there,” he contends. Sure enough, there was evidence aplenty. Mapping by Dawn’s GIS unit shows that the fish farms — which require sweet water — cover an area of 350 acres on the right bank of the Keenjhar-Gujjo canal and 305 acres on the left bank.

On the day of Dawn‘s visit to the site, the gauge, which has a maximum limit of 9ft 4 inches, shows the water in the canal at 8ft 1inch. Mohammed Sultan, a KWSB employee whose job is to trim the trees and bushes along the canal so no vegetation falls in, says the last time he saw the water released to 9ft in the canal was around the time he was employed with the water board some 35 years ago. “There’s plenty of water. But the infrastructure ahead can’t handle it. The pipelines will burst.“

At the other end of Karachi’s water supply system, in district West, is the Hub pumping station for water from the Hub dam and K3. “Wapda is the custodian of the first 5km of the Hub canal, after which, at ‘zero point’, the canal carrying the water bifurcates with one branch coming into Sindh which is the KWSB’s responsibility,” says Fahad Siddiqui, assistant executive engineer at the Hub pumping station.

“We have the capacity to pump 200MGD if Wapda gives permission, but the quota for Karachi from Hub is only 100MGD.”

For his part, MD, KWSB Mr Ahmed tells Dawn he is overseeing a change in the running of the organisation, with digitised systems and streamlined procedures to make it easier to track the situation on the ground instead of the manual system which is more conducive to corruption.

“I’m shrinking their space,” he says. However, even with the World Bank’s soon-to-be-launched $1.6bn project to overhaul KWSB, Mr Ahmed believes “it isn’t possible to revamp the entire infrastructure. Look at the enormity of the task. Even $10bn wouldn’t suffice. Only the gaps can be bridged.”

The SC-mandated commission on water and sanitation in Sindh made 100 recommendations to improve service delivery in these sectors. According to Shahab Usto, the lawyer whose petition started the process, only one of the recommendations has been implemented.

“The then chief justice, Gulzar Ahmed, dissolved the commission [in 2020] within minutes, without giving me an opportunity to be heard,” he says. “The body should have remained in existence to ensure that all its recommendations were implemented.” He plans to file another petition so that work on those measures can be resumed.

Meanwhile, Pakistan’s largest city continues to be held hostage by a mercenary cabal for whom the misery endured by the residents because of water scarcity is simply the means to political clout and untold riches.