There was a time when Peshawar was known as the city of flowers. Perhaps this was because of the many gardens built in the 16th and 17th centuries during the Mughal Era.

Professor Sayed Amjad Hussain wrote in the September 7, 2018 issue of The Friday Times that, “At one time, Peshawar was known by her monikers ‘City of Flowers’ and ‘City of Seven Colours’. In a not-too-distant past, the arrival of spring was heralded by flower-sellers balancing large baskets of roses on their heads and walking through the labyrinthine streets of the old city and shouting ‘It is the spring of roses, come and get fresh roses’.” Flowers, including roses, were cultivated in the surrounding villages on the outskirts of the city.

The city’s name is believed to have been derived from the Sanskrit name for ‘city of flowers,’ Poshapura, a name found in an ancient Kharosthi inscription that may refer to Peshawar. According to researcher and writer Mohammed Ibrahim Zia, in his book Peshawar Maazi ke Dareechon Mein [Peshawar Through the Windows of the Past], during the Durrani rule in 1809, Scottish statesman and historian Monstuart Elphinston spent about four months in Peshawar. In his memoir Account of the Kingdom of Caubal, Elphinston describes fruit and flower gardens, springs and date trees in the northern areas of Peshawar, where dates couldn’t ripen because of the cold.

Zia also describes that when Zaheeruddin Babar invaded the Khyber Pass in 1505 and stayed in Peshawar in 1519, he saw people working in fields around the city that had trees and flowers.

Dr Noor ul Amin, professor of Landscape and Floriculture at the University of Agriculture, Peshawar, points out that the city is still home to several large gardens such as Wazir Bagh and Shahi Bagh from the Mughal era, and Cunningham Park (now known as Jinnah Park) and Company Bagh from the British era.

But in 2016, the World Health Organisation (WHO) ranked Peshawar as the second-most polluted city across the globe. This revelation is borne out by readings from IQAir, a real-time air quality information platform. Emissions and fumes from vehicles are the main causes of air pollution in Peshawar. Numerous cars, motorbikes and rickshaws populate the city roads, along with heavy-duty vehicles such as trucks and lorries, many of which run on diesel, or fuels of considerably lower quality.

Peshawar’s traffic police estimates that about 700,000 vehicles enter and exit the provincial metropolis on a daily basis, while 35,000 registered two-stroke and four-stroke auto-rickshaws ply the streets and add more pollution to the city.

Research on the emission of greenhouse gases in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) by Dr Asif Khan, a PhD scholar at the University of Cambridge, reveals that the emission of these gases is highest in the transport sector. His research for the Pakistan Forest Institute shows that the emission of greenhouse gases is the most in Peshawar, followed by Mardan, Dera Ismail Khan and Abbottabad.

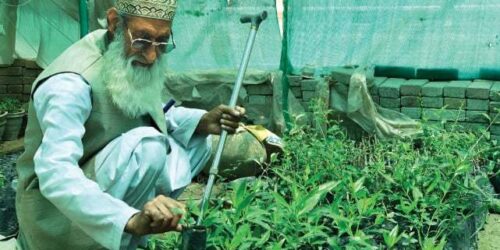

In such a dire situation, one man has flown the green flag. Blaming Peshawar’s abrupt urbanisation, high-rise buildings, shopping plazas and markets for the city’s ever-increasing pollution, 70-year-old Misal Khan has pledged to make Peshawar a city of flowers again.

“Peshawar was once full of flowers and you could see them on roadsides, in gardens and homes,” he says. “We need more greenery in this city, but there seems to be no respite in this concrete jungle.”

Khan, who previously worked as director physical and health education at Hazar Khwani Government Higher Secondary School, spent over 20 lakh rupees in 2017 — including his gratuity — to establish a nursery at Gulbahar, a few metres away from the Grand Trunk or GT Road, the city’s main thoroughfare. After coining the slogan ‘Your Pot, My Plant’, he has distributed nearly 200,000 saplings of flowers and plants to people across the province, free of cost.

“Almost 100,000 plants were given to Peshawar’s Town-1, Town-2 and Town-3 on the request of the government in 2017,” he says. “Sadly, the government has ignored my requests for a maali [gardener] to assist me because I am growing old.”

A variety of plants and flowers, including some evergreen species as well as grape vines and pomegranate, guava and loquat saplings, are available at Khan’s nursery.

Khan recalls how he once complained to his father about people cutting trees near his home and his father had replied, “Don’t worry too much about trees being cut, instead plant two trees.”

Khan’s four daughters work for the government, while one son is a doctor and the other a businessman in Canada, who takes care of the family, leaving Khan at leisure to pursue his passion for plants.

He has named his nursery after Abdur Rahman Baba, the Pashto Sufi poet. Khan is also known as a ‘pir’ because of his passion for Rahman Baba’s poetry. He has put up a few posters in his nursery with Rahman Baba’s poetry on them.

Khan admits that he may not be able to make the entire city green but wants to do as much as he practically can. He has also published a few booklets on climate change to hand out to people, to create awareness about the importance of greenery for the environment.

Khan wants Peshawar’s residents to help him in his mission in giving the city flowers and greenery which will help fight pollution. “Neither the government, nor the people have any interest in cleaning up Peshawar’s environment,” says Khan a bit despondently. “They would rather wear a mask and inhale polluted air, but no one will make any effort to plant a tree or flowers for their own benefit.”

But Hastam Khan, whose family is associated with the nursery business for the last 35 years, believes that Peshawar still has the potential to grow good quality flowers and hence can revive its past glory of being a city of flowers. He is pleased that social media has created climate change awareness and that there are Facebook and WhatsApp groups through which young people purchase flowers and plants online.

“People should also be growing their own food,” he says. “Instead of growing fruit and vegetables, people have turned gardening into a luxurious hobby and prefer growing hybrid plants because importing originals is very expensive,” he says. “The government should look into developing new environment-friendly and affordable hybrid plants and trees.”

Having been witness to Peshawar’s beautiful floral past, the two Khans hold out hope that the government will yet help them establish nurseries at a district level across the province.