Huge swarms of desert locusts are wreaking havoc in parts of East Africa, Asia and the Middle East, threatening crops, livelihoods and food supplies. It is already the worst locust infestation in decades, but the forthcoming rainy season could see numbers increase a further 20-fold in some places if swarms are not tackled.

Desert locusts, like this one, typically live in the arid areas of about 30 countries between West Africa and India – a region of about 16 million sq km (6.2 million sq miles).

A type of grasshopper, they generally live shy, solitary lives.

And they can continue this unremarkable existence for years.

But every now and then, desert locusts undergo a Jekyll and Hyde transformation.

When they get crowded together – such as on diminishing areas of green vegetation after rains give way to drought – they stop being solitary creatures and become “gregarious” mini-beasts.

When desert locusts begin to group together, a brain chemical called serotonin is released into their bodies, triggering a series of changes in their appearance and behaviour.

The insects not only change colour, becoming brighter, but also get faster, more hungry and extremely sociable.

Once in this “gregarious” phase, locusts actively seek out the company of their fellow insects, start reproducing explosively, and form groups that can develop into huge marauding swarms.

These huge swarms can contain up to 10 billion individuals and stretch over hundreds of kilometres.

Even an average swarm can destroy crops sufficient to feed 2,500 people for a year, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

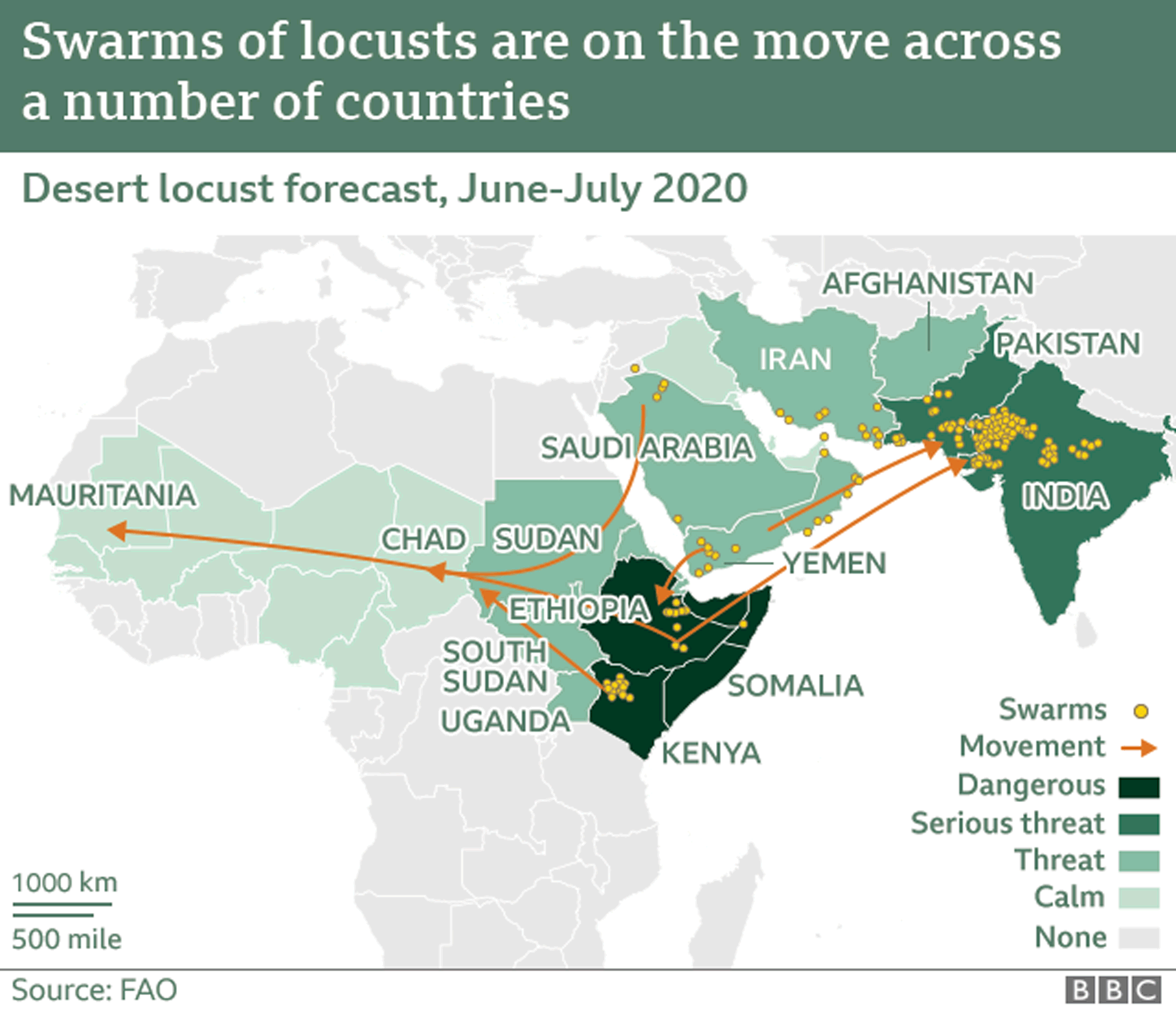

Such ravenous swarms are now building up across East Africa, Yemen, Iran, Pakistan and India – and the area has been warned to be on “high alert” by the FAO.

Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia, which have already experienced the worst swarms of locusts in decades, continue to face an “unprecedented threat”, the FAO says. There is also a risk they could spread to West Africa.

But the growing and migrating swarms are also now attacking vegetation in parts of the Middle East and Pakistan, as well as threatening crops in India.

And the number of locusts could increase 20 times in the forthcoming rainy season in South Asia, the FAO warns, unless extra measures to counter the swarms are put in place.

Making matters worse, many of the affected countries are already suffering from the effects of protracted crises – flooding, conflict and now the coronavirus outbreak.

“With Covid-19, it is now a double pandemic to our people,” says Albert Lemasulani, a herdsman and locust tracker from northern Kenya. “Wherever they descend, they eat virtually everything. It’s a nightmare.”

The causes of the current infestation go back to the cyclones and heavy rains of 2018-19.

The wet, favourable conditions two years ago on the southern Arabian Peninsula allowed three generations of locusts to flourish undetected, the UN says, and a locust boom followed.

Despite ongoing control operations in several countries, recent heavy rains have led to ideal conditions for the pest’s further reproduction.

Another generation of locust eggs is hatching, just as farmers in the region are beginning to harvest. This will exacerbate an already bleak food security situation in many countries, especially in East Africa, the FAO says.

The organisation is raising funds to step up control operations, but, for some, spraying has come too late.

Farmers across northern Kenya and beyond have already lost everything to the swarms.

“Every day, you get five, six, seven, 10 swarms,” says Mr Lemasulani, who runs a team of volunteers coordinating the response alongside the UN and Kenyan government. “If this continues, we will be done. Our life will be done.”