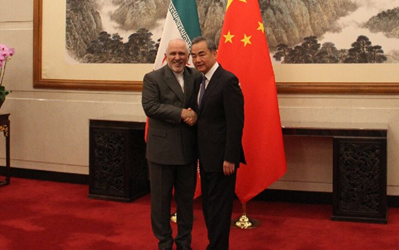

At the end of August, Islamic Republic of Iran (IRIN) Foreign Minister Mohammad Zarif visited Beijing for what appeared to be a routine visit. However, soon after the visit, it was reported in the media that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) had agreed to invest a vast sum of $400 billion in Iran. This would be the biggest investment that China has pledged to any one country as a part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). According to the details of the agreement, China has pledged to invest $280 billion in the oil, gas, and petroleum sector of Iran. In addition to this, Beijing has also announced an investment of $120 billion in the transportation infrastructure of Iran. It was further revealed that these amounts will be invested in the first five years of the agreements, and that further investments can also be made if both parties agree. The PRC has also announced its intent to continue importing oil from Iran despite the imposition of sanctions by the U.S Government

Per the available details, Chinese companies will be provided the first right of refusal in all of the projects in which China is investing—meaning that Chinese companies will be offered the projects first, and only after their refusal will the projects be made open for bidding by companies from any other country. Another particularly striking aspect of the agreement is that the PRC will reportedly station around 5,000 security personnel in Iran to protect its investments—the first time that China has openly asked for such a large security presence in any agreement with a BRI participant country (The Nation (Pakistan), September 9).

Has the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Been Shelved?

In April 2015, the PRC signed the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) agreement with Pakistan. CPEC, valued at $62 billion, was dubbed as the flagship project of the BRI. It started with much fanfare, and China pinned many hopes on the project, expecting CPEC to provide trade connectivity between China and the Arabian Sea, and consequently to the Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf (Xinhua, May 11, 2017). CPEC was on track until mid-2018, when a transfer of power in Pakistan changed everything: the new government of Pakistan under the leadership of Prime Minister Imran Khan effectively took steps to scale down CPEC (Nikkei Asian Review, June 17).

Chinese officials have taken notice of the change of heart in Pakistan with regards to CPEC. China has reportedly cut down the funding for CPEC projects after cabinet ministers in Pakistan started criticizing CPEC. Due to a lack of funds, the government of Pakistan had to stop working on multiple projects. Now, work on most of the CPEC projects has been suspended and the program has lost its momentum (The News (Pakistan), September 17). This is nothing less than a major shock to the PRC’s global Belt and Road machine. Therefore, it is natural that Beijing would look or alternative options to advance its interests in the region.

An Emerging “China-Iran Economic Corridor”?

Since losing hope in the success of CPEC, China has looked further south to Iran, which enjoys many of the same strategic advantages as Pakistan. Iran has a long coastline in the Persian Gulf, and it controls one part of the coast in the narrow Strait of Hormuz. Furthermore, Iran, like Pakistan, can access transit routes into Central Asia through Afghanistan. From Beijing’s perspective, the only negative point to Iran’s geography is that the country does not have direct land access to China. However, even this can be compensated for by Iran’s direct land linkages to Central Asia—including routes that could bypass Afghanistan in the event that peace does not return to that troubled country. Therefore, China has decided to place its bets on what might be called a “China-Iran Economic Corridor.”

The proposed PRC investments in Iran will serve two purposes. The investments in the oil and gas sector will support the struggling economy of Iran, and provide that major Middle Eastern country with an incentive to cooperate with China. Secondly, the investment in transportation infrastructure will develop the road and railway networks necessary to connect China with the Persian Gulf through the ports of Chabahar and Bandar Abbas.

Another key element to this story is the construction of railway lines connecting Afghanistan with China via the Central Asia states of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. The first train with 41 cargo containers successfully traveled from Afghanistan to China in September this year (Azer News, September 6). China can use this connection to transport goods to and from Iran; however, it will first need to develop transport infrastructure connecting Iran with Afghanistan. This requires peace in Afghanistan, and for that purpose, the PRC hosted Taliban leaders for September meetings in Beijing to contribute towards attaining peace in the country (SCMP, September 23).

How Realistic is the China-Iran Corridor?

Most of China’s BRI projects have been over-ambitious, and there have always been question marks surrounding their ultimate prospects. CPEC is one such example: it was touted as a game-changer for Pakistan, but it did not rise to the high expectations created around it. Therefore, it is important to consider how realistic the proposed China-Iran Corridor might prove itself to be.

First of all, the China-Iran deals are almost seven times bigger than CPEC in terms of valuation. The $62 billion CPEC has faced a plethora of economic and political problems in the last three to four years. In this context, a $400 billion project will face even more obstacles than CPEC. It would be a gigantic economic venture, and its timely completion will be a huge challenge for both parties concerned. Secondly, the geopolitical situation of Iran is more volatile than that of Pakistan. Iran is facing sanctions and even the threat of armed conflict with the United States. Iran’s government is also heavily invested in sponsoring Shiite groups from Yemen to Lebanon—and in connection with this, Iran has locked horns with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, one of the most powerful states in the Middle East. All of this means that Iran has a lot of enemies who may potentially try to sabotage the progress of this over-ambitious economic corridor to China. Therefore, it will be difficult for the PRC to ensure the smooth progress of this project.

The Reaction of Pakistan

The incumbent government of Pakistan has changed the policies of the erstwhile government on CPEC. PM Khan’s government has not only scaled CPEC down, but has treated it as a low priority project; in doing so, it not only killed the momentum of CPEC, but also earned the ire of Beijing. Things were going reasonably smoothly for the current government of Pakistan until India’s surprise move on August 5, when it suspended the special status of Kashmir and made it union territory (Xinhua, August 5). This put the government of Pakistan on its back foot diplomatically, and made it feel more keenly the need for support from China. However, at that point Islamabad had already shelved CPEC, so it was difficult to convince the PRC to continue providing help to Pakistan.

Against this backdrop, Pakistan started in September to make a fresh push to renew CPEC. The government of Pakistan has used special powers and bypassed the parliament to establish a CPEC authority, which is supposed to fast track the work on CPEC projects while overriding the normal legislative checks (Dawn, October 8). Pakistan also announced a 23-year tax holiday for Chinese companies running the port of Gwadar. These steps have been complemented by a Pakistan government public relations campaign promoting the message that CPEC has been revived. Pakistan has doubled down its efforts to revive CPEC in order to earn back the trust and support of China.

This change of heart by Pakistan is also due in part to the announcement of the China-Iran Corridor. Pakistan’s decision-makers have realized that they lost their status as China’s favorite client in the region. From 2015 to 2018, Pakistan was the main regional player on which China was betting; now, due to Pakistan’s own policies, Iran has entered the picture to the detriment of Pakistan. If Pakistan does not mend fences with China, then it could further lose support from its so-called “Iron Brother”. So, the fear of losing its advantageous geopolitical status to Iran made the government of Pakistan up the ante on CPEC. However, the abrupt manner in which the government of Pakistan took this step triggered a domestic political crisis: the opposition in Pakistan has rejected the establishment of the new CPEC authority, and this will further make CPEC controversial (Dawn, October 9). Still, the government will pursue these decisions in order to ensure that Pakistan does not lose its coveted place in the BRI.

Conclusion: What Is the Future of the China-Iran Corridor?

This proposed corridor will likely prove to be very beneficial for Iran. It will provide Iran with diplomatic and economic support at a time when the Trump Administration is making an effort to isolate Iran as an international pariah. This series of projects could not only upgrade the oil and gas sector of Iran, but could also develop transportation infrastructure in the country, which will further develop Iran’s overall economy. However, all of these benefits can only be realized if China actually fulfills its commitments; in the past, the PRC has been known to make exaggerated claims regarding its investments in other countries. CPEC is one example in which there is no documentary proof that China will actually invest the claimed amount of $62 billion—and therefore, there is no guarantee that China will actually invest $400 billion in Iran.

Moreover, security could prove to be a major stumbling block for the progress of this corridor. Given Iran’s strained relations with Saudi Arabia and the United States, there is no guarantee that Iran will not face military conflict in the near future. In such a scenario, all the investments of China would be endangered, and therefore this point will be carefully considered by Beijing before investing a single yuan. Still, there is no denying the fact that China has decided to take a gamble in Iran—one that could potentially have a dramatic impact on the economic and geopolitical course of the Middle East and South Asia.